Highlights from the The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

28 Jul 2025

The Met’s reimagined Michael C. Rockefeller Wing reopened in May 2025 after a multiyear renovation. Home to the arts of Africa, the ancient Americas, and Oceania, the new presentation treats these collections as distinct while deepening their connections to global art history. Originally opened in 1982, the wing was among the first at The Met to centre non-Western art. Today, its renewed vision is shaped by contemporary research and international collaboration, offering a more layered and inclusive view of each collection. Below, the Met’s curatorial team share some of their highlights from each section.

Arts of Africa

This gallery brings together around 500 works from across sub-Saharan Africa, presented through the lens of major artistic movements and living traditions that continue to shape the region’s visual culture.

The Seated Figure was created over 700 years ago in the Inland Niger Delta region of present-day Mali. It comes from Jenne-jeno, the oldest known city in sub-Saharan Africa, once a thriving urban centre that flourished in the ninth century. With its bowed head and tightly drawn limbs, the figure captures a moment of deep inwardness, evoking both spiritual reflection and physical vulnerability.

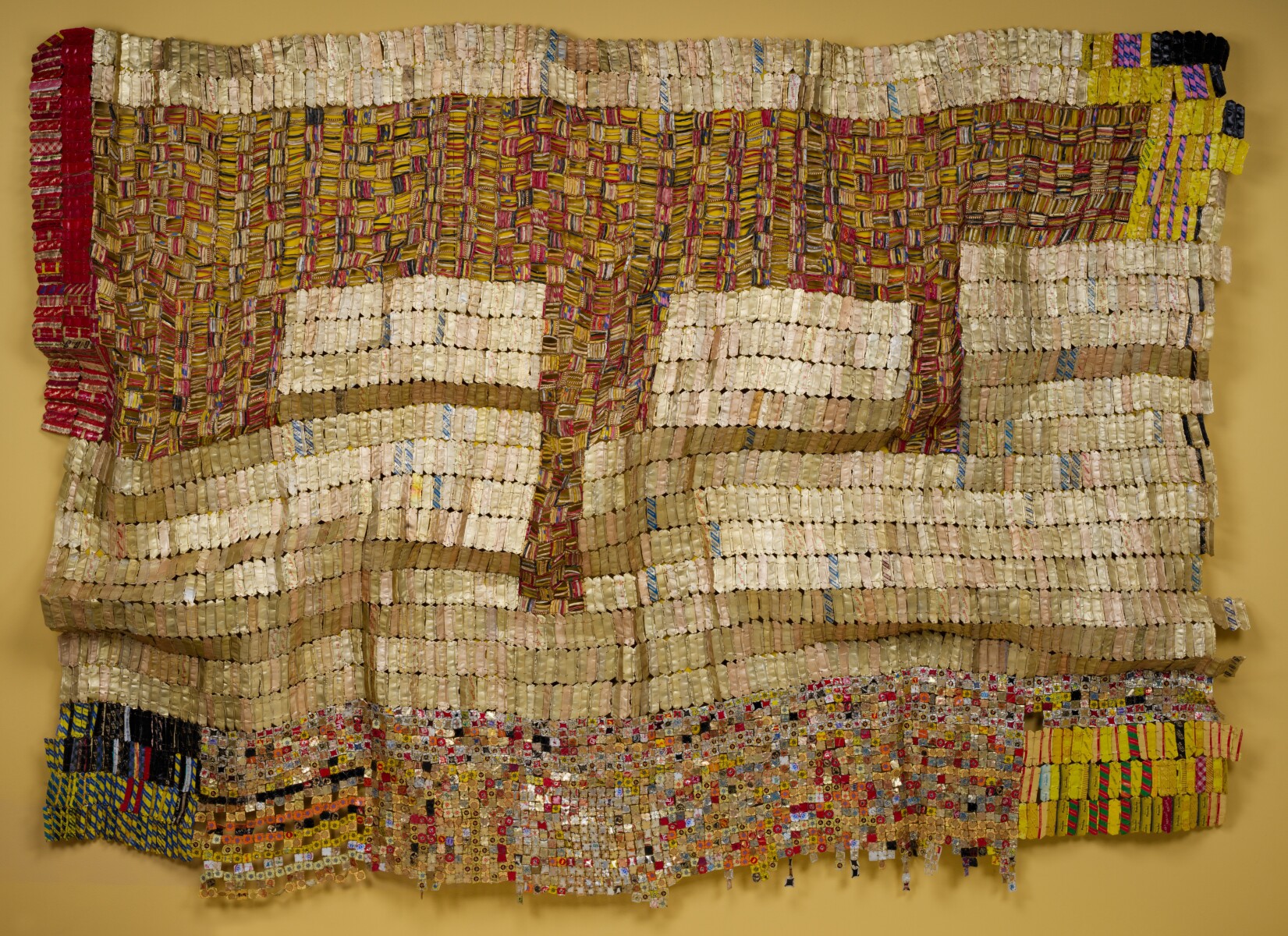

Between Earth and Heaven by contemporary Ghanaian artist El Anatsui is a monumental metal tapestry inspired by the tradition of West African strip-woven textiles, particularly the Kente cloth of the Akan and Ewe peoples. Replacing silk with bottle caps and flattened metal fragments, the work transforms the language of textile into sculptural form. Its rippling surface and vibrant palette reflect both the grandeur of ceremonial dress and the ongoing dialogue between tradition and contemporary practice.

The Mangaaka Power Figure (Nkisi N’Kondi), created by a Yombe-Kongo artist and nganga, dates from around 1880 to 1900. This figure exemplifies the powerful tradition of Kongo minkisi, ritual objects conceived to house spiritual force. Created through collaboration between Kongo sculptors and ritual specialists, it represents Mangaaka, a force of law and protection. Its assertive stance, metal-studded torso, and traces of medicinal materials show that it once served as both guardian and witness in community affairs, embodying justice, authority and the consequences of broken vows.

Arts of the Ancient Americas

Nearly 700 works from Indigenous cultures across North, Central and South America and the Caribbean are presented here, highlighting the creativity and complexity of these civilisations before 1600 CE. The installation reflects ongoing research into the ancestral arts of the Americas.

The Feathered Panel was unearthed in 1943 in southern Peru’s Churunga Valley. A cache of nearly one hundred feather panels remains one of the most extraordinary discoveries of Precolumbian Andean art. Preserved in ceramic jars and buried in arid soil, each panel is densely covered in vibrant blue and yellow macaw feathers sourced from the Amazon, hundreds of miles away. The scale and craftsmanship suggest these feathers held immense value, though the panels’ exact function continues to elude scholars.

The Serpent Labret with Articulated Tongue was created in the Aztec Empire before the Spanish conquest. This gold labret was worn through the lower lip as a symbol of royal authority and sacred speech. Its intricate form, including a moveable tongue, may represent Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent linked to the sun god Huitzilopochtli. As one of the few surviving examples of Aztec goldwork, it speaks to a world nearly erased by colonisation.

The Standing Female Figure from the Huasteca region stands with quiet poise, her hands resting gently on her abdomen and her face finely carved with serene detail. She wears an elaborate headdress with celestial symbolism, a marker of elite status shared by both women and men in Huastec society. Thought to represent solar, lunar or stellar rays, the headdress links her to political and possibly cosmic authority.

Arts of Oceania

With more than 650 works on view, this gallery represents over 140 cultures from across the Pacific, including monumental works from New Guinea, coastal archipelagos, Australia, and Island Southeast Asia. The installation celebrates the region’s cultural breadth and shared ancestry, spanning almost one-third of the planet’s surface.

The Ceremonial House Ceiling was created by Kwoma artists in the village of Mariwai during the early 1970s. It features over 270 paintings commissioned by Douglas Newton, the first curator of Oceanic art at the Metropolitan Museum, and installed as an 80-foot-long art installation. Kwoma ceremonial houses are known for their vast, steeply pitched roofs without walls. These serve as sacred spaces for male rites and community gatherings. The ceilings of the most ornate houses are decorated with hundreds of brilliantly coloured paintings representing clan-specific images of supernatural beings, animals, plants, and abstract clan symbols. Each painting is crafted on cured bark or sago palm petioles, combining figurative and geometric designs whose meanings vary according to clan and artistic intent.

The Body Mask created by an Asmat artist in the mid-20th century was made for a jipae, a feast that guides the spirit of the deceased into the ancestral realm of safan. Constructed from woven fiber, rattan, feathers and seeds, and worn in a ritual performance, each mask embodies a specific ancestor and is activated through dance, hospitality and symbolic return. This example, collected by Michael C. Rockefeller in 1961, reflects the profound artistry and spiritual depth of Asmat ceremonial life.

Headrest from the Tami Islands, dating to the mid to late 19th century, comes from a region connected by a complex maritime trade network in which ritual objects, designs, and ceremonies circulated alongside everyday goods. The Tami Islands, located off the Huon Peninsula, became the most prolific and influential centre of art production in the region. Tami objects and designs circulated widely, creating a shared aesthetic so pervasive that the region’s artistic traditions are often called the Tami style. However, artists in each culture adapted this shared artistic vocabulary to create their own distinctive imagery.