Highlights from the The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

28 Jul 2025

The Met’s reimagined Michael C. Rockefeller Wing reopened in May 2025 after a decade long renovation project. Home to the arts of Africa, the ancient Americas, and Oceania, the new presentation treats these collections as distinct while deepening their connections to global art history. Originally opened in 1982, the wing was among the first at The Met to centre non-Western art. Today, its renewed vision is shaped by contemporary research and international collaboration, offering a more layered and inclusive view of each collection. Below are highlights from each of these major fields of world art presented within The Met’s new wing.

Arts of Africa

This gallery brings together around 500 works from across sub-Saharan Africa, presented through the lens of major artistic movements and living traditions relating to some 170 distinct cultures.

Seated figure, Middle Niger artist, 13th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Buckeye Trust and Mr. and Mrs. Milton F. Rosenthal Gifts, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest and Harris Brisbane Dick and Rogers Funds, 1981.

This seated figure was created over 700 years ago in the Inland Niger Delta region of present-day Mali. It relates to the ancient city of Jenne-jeno, one of sub-Saharan Africa’s early urban centers settled as early as 300 B.C.E that flourished as a thriving center of trade from the ninth century. With its bowed head and tightly drawn limbs, the figure captures a moment of deep inwardness, evoking both spiritual reflection and physical vulnerability.

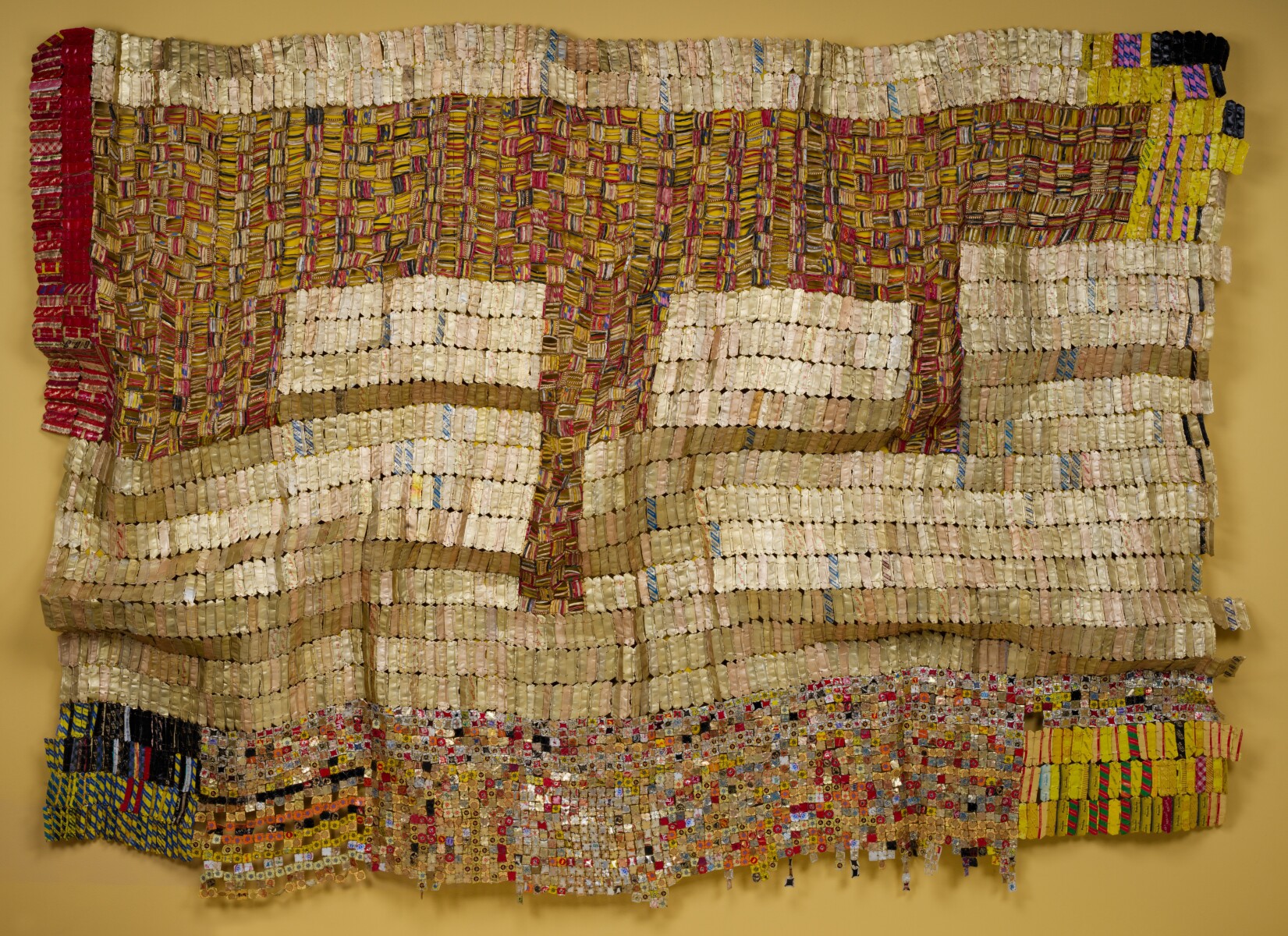

El Anatsui, Between Earth and Heaven, 2006. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © El Anatsui. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Between Earth and Heaven by contemporary Ghanaian artist El Anatsui is a monumental metal tapestry inspired by the tradition of West African strip-woven textiles, particularly the Kente cloth of the Akan and Ewe peoples. Using recycled aluminium bottle caps and flattened metal fragments, the work transposes the palette and formal language of those textile genres into and original idiom. Its rippling pliable surface evokes the fluidity and dynamic movement of monumental textiles on the body and comments on the historical nature of exchange between West Africa and Europe.

Mangaaka Power Figure (Nkisi N’Kondi), Yombe-Kongo artist and nganga (ritual specialist), Kongo artist and nganga, Yombe group, ca. 1880–1900. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace, Drs. Daniel and Marian Malcolm, Laura G. and James J. Ross, Jeffrey B. Soref, The Robert T. Wall Family, Dr. and Mrs. Sidney G. Clyman, and Steven Kossak Gifts, 2008.

The Mangaaka Power Figure (Nkisi N’Kondi), the collaborative creation of a Yombe-Kongo sculptor and healer or nganga, dates from the final decades of the nineteenth century. This figure exemplifies the powerful tradition of Kongo minkisi, ritual instruments conceived as vessels for specific mystical forces. This monumental example represents Mangaaka, a force of law and protection. Its assertive stance, metal-studded torso, and traces of medicinal materials show that it once served as both guardian and witness in community affairs, embodying justice, authority and instilling in viewers the consequences of broken vows.

Arts of the Ancient Americas

Nearly 700 works from Indigenous cultures across North, Central and South America and the Caribbean are presented here, highlighting the artistic legacy of Indigenous artists before 1600 CE. The new installation reflects ongoing research to present a more encompassing view into the ancestral arts of the Americas.

Feathered panel, Wari, 600–900 CE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979.

In 1943, a cache of ninety-six feathered panels were found in southern Peru’s Churunga Valley. Preserved in ceramic jars and buried in arid soil, each panel is densely covered with tens of thousands of vibrant blue and yellow macaw feathers sourced from the Amazon, hundreds of miles away. The scale and craftsmanship suggest these feathers held immense value, though the panels’ exact function continues to elude scholars.

Serpent labret with articulated tongue, Mexica artist(s), 1325–1521 CE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 2015 Benefit Fund and Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2016.

The serpent labret with articulated tongue is a rare survival of what was once a thriving tradition of gold-working in the Aztec Empire. Gold, in Mexica belief, was teocuitlatl—godly excrement closely associated with the sun’s power. This labret was worn through the lower lip as a symbol of royal authority and speech. Its intricate form, including a moveable tongue, may represent Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent linked to the sun god Huitzilopochtli.

Standing female figure, Huastec artist(s), 1250–1521 CE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mary McFadden, 2024.

This standing female figure from the Huasteca region stands with quiet poise, her hands resting gently on her abdomen and her face finely carved with serene detail. She wears an elaborate headdress with celestial symbolism, a marker of elite status shared by both women and men in Huastec society. Thought to represent solar, lunar or stellar rays, the headdress links her to political and possibly cosmic authority.

Arts of Oceania

With more than 650 works on view, this gallery represents over 140 distinct cultures from across the Pacific, including monumental works from New Guinea, surrounding coastal archipelagos, Polynesia, Australia, and Island Southeast Asia. The new installation celebrates the region’s cultural breadth and shared ancestry, spanning almost one-third of the planet’s surface.

Ceremonial House Ceiling, Kwoma people, 1970–1973. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Purchase, Mrs. Gertrud A. Mellon Gift, and Mr. and Mrs. Alan Brandt Gift, in memory of Jacob J. Brandt, 1974, Purchase, Rogers Fund and Mr. and Mrs. David Nash and Anonymous Gifts, 1975. Photo by Paula Lobo.

A new configuration of the iconic Kwoma Ceremonial House Ceiling features 182 individually painted panels. The display evokes the of vast, steeply pitched roofs of the houses that serve as sacred spaces for male rites, meetings, and informal gatherings in the Sepik River region of Papua New guinea. The ceilings of the most ornate houses are decorated with hundreds of brilliantly coloured paintings representing clan ancestors, animals, plants, and abstract clan symbols. Each painting is crafted on cured bark or sago palm petioles (pangal), combining figurative and geometric designs whose meanings vary according to clan and artistic intent. This set of pangal is distributed according to clan group in accordance with the present-day wishes of the descendants of the Kwoma painters who worked on the original commission of this piece.

Body mask, Asmat artist, mid-20th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller and Mrs. Mary C. Rockefeller, 1965.

This body mask created by an Asmat artist in the mid-20th century was made for a jipae, a feast that guides the spirit of the deceased into the ancestral realm of safan. Constructed from woven mulberry fiber, sago palm leaves, feathers and seeds, and worn in a ritual performance, each mask embodies a specific ancestor and is activated through dance, hospitality and symbolic return. This example, collected by Michael C. Rockefeller in 1961, reflects the profound artistry and spiritual depth of Asmat ceremonial life.

Headrest, Tami Islands, mid to late 19th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979.

This headrest from the Tami Islands, dating to the mid to late 19th century, comes from a region connected by a complex maritime trade network in which ritual objects, designs, and ceremonies circulated alongside everyday goods. Tami carvers produced large quantities of objects, in part for local use but primarily for trade to neighbouring groups. The Tami Islands were known as the center of headrest making in the region, and headrests themselves were valued possessions. Following the death of a family member, relatives would go to chew betel at their place of residence and invite the departed to come and claim their personal headrest and betel pouch to take with them to the afterlife.